How a husband and wife team made a film about speaking to your family about being a survivor

It’s rare that you come across a film that feels groundbreaking. When filmmaker Hossein Behboudi Rad decided to tell his parents about the abuse he experienced as a child, he knew he wanted to make a documentary about it.

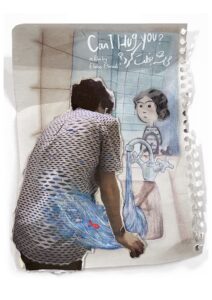

Together with his wife and director Elahe Esmaili (The Doll, One World Media alumni), they made Can I Hug You?, a moving short film that asks the question: are we ready to support the survivors in our lives?

In the city of Qom, the most restricted city in Iran, there are many restrictions on human rights, such as mandatory hijab to assure ‘sexual safety’. Hossein grew up in this environment and experienced multiple sexual assaults by men, despite these measures. Due to stereotypes around masculinity, he never talked about it. With the support of his wife, Elahe, he confronts the trauma in this beautiful short film. Can I Hug You? was developed as part of One World Media’s Global Short Docs Forum.

In this revealing conversation, Hossein and Elahe tell SurvivorsUK about how making Can I Hug You? has been a healing experience, their hopes for this film to open up conversations about supporting survivors, and how making this film has been a milestone in their relationship.

—

Why did you choose to make a film tackling this subject?

Hossein: For a very long time I have been looking to see a film on this topic, about child abuse and male victims, especially. But I couldn’t find any. Also, a film that focusses on that topic specifically on our region in Iran where there are a lot of serious gender rules and human rights violations in our society that I have been witnessing since my childhood. Whenever I would ask my teacher or my parents why we have all these rules, they would always tell me that it was for the sexual safety of society. But I knew that our society was not safe, because of the abuse that happened to me as a child.

So when my therapist told me that I needed to talk about this with my parents, I said, okay, if I’m going to talk about this with my parents, then I’m going to make it into a film. There have been a lot of conversations about MeToo and films, but rarely talking about male victims. All of this contributed to me feeling much more isolated. So I wanted to make a film for anyone who feels alone like me, or anyone who wants to talk about these experiences but isn’t ready yet to talk about their own experiences.

I also wanted to criticise all those human rights violations in Iran. Especially now that women are having more freedom in Iran, it’s more important to emphasise that all of these human rights violations are not working and are just patriarchal restrictions imposed by the government and the regime. So there were a lot of things that sparked this film. I don’t know if you want to add anything?

Elahe: For me, it was really important to talk about this subject because as women and young girls we experience a lot of restrictions. When we’re young our parents stop us from doing social activities to stop these kinds of abuse, and when we’re adults society imposes hijab on us, again, to stop these things from happening. But I wanted to say, this is not how it works. Boys are also having difficulties and restricting us is not the solution.

You introduce those themes really beautifully at the start of the film, showing young men being taught in a classroom that these measures are for the safety of the community. It feels like responsibility for personal safety and preventing abuse is put very much on the individual or victim, rather than on the community to challenge behaviours and attitudes that might cause harm.

Elahe: Yes. Women are told to make the society safe for men, and I think that’s how the patriarchal systems work. As a woman, if you were raped or sexually assaulted, it’s because it’s your fault. In our society, it would be because “you didn’t cover yourself properly and that’s why you were raped.” They don’t face it in the right way, or find solutions that hold the person accountable who made this community unsafe for me.

Hossein: At the same time, that attitude of placing blame on the victim is true for men as well as women. Since that’s way society views victims, all the time in the back in my mind I know that if I tell someone that somebody abused me, they’re going to say, “What did you do? How did you behave that they did that to you? Why didn’t you tell them no?” All the time, I’m thinking that I am the person who has done something wrong, or that I’m responsible for what happened. At least for myself, I know this is the feeling that I had and received from society.

You show a flashback of one of the instances of abuse Hossein experienced as an animated sequence, like a child’s drawing. Was it a challenge to find a sensitive way of showing what happened?

Elahe: Yes, I wanted to show that part of the story as well, but I didn’t want it to be explicit. Instead, I wanted to convey the emotions and try to express how one feels when that happens. Apart from the violence, I wanted to show the nature of that pain. So animation helped me to explore those emotions that I wanted to achieve and it added another layer to the story as well.

Hossein: As Elahe mentioned, it’s very important how you want to depict those things, because sometimes if you are a victim or even a family member it can be very hard to see those violent scenes. It was very hard for me to tell my parents, so I think Elahe made a really good decision there to make it into animation. At the same time, she is also narrating those scenes from her perspective, so it helped and was better for me that I did not need to talk about all those violent scenes.

Did society’s ideas of masculinity make it difficult for you to talk about your experiences as a victim of abuse?

Hossein: It made it very hard and I think that was the reason why I felt so isolated, and why I kept so silent. We talk about this in the film, but when everybody expects you to be strong and protect others, but not be protected yourself, it’s very hard to talk about being violated It was very damaging and it made it very hard to even decide to talk about, even with the help of my therapist. The sad thing is we don’t talk a lot about toxic masculinity, and even if we talk we need to go beyond that. We need to redesign and redefine a new identity for men, that goes beyond the limits of current social expectations of what it means to be a man.

When I think about what I was taught about what it is to be a man, all the stuff that I remember is to be a strong person, to protect your family, protect your children. So the identity of a man is defined by social expectations. For me as a man, I think all of these definitions are not true and are making everything harder for men to seek any kind of help.

At the same time, these definitions don’t just affect men, but they affect women as well, because if I think men have to be strong then I’m unconsciously thinking that women are weak, which is not true. So I think we need to redefine male identity. And yes, it was very damaging for me, and I’m really thankful to Elahe and to my therapist, every person who tried to help me understand that these toxic ideals are not the case.

Elahe, how did you feel when Hossein first told you about the abuse he experienced as a child?

Elahe: Honestly, it was really hard for me. I didn’t know how to respond to because I wasn’t educated either. I just tried to support him from the beginning. The first time that he told me I could feel that it was really hard for him to describe, like some of his memories were ripped apart. He couldn’t even say it – he wrote everything and shared it in a Google Doc with me, saying “this is what happened to me and how I feel about it.” Because I was always questioning that you are a bloody successful man, you’re great at your job, you do great at everything you do – why do you not feel confident? Why do you always think you’re not worthy or not good at your job, because this is not true? I was always questioning that.

So then he sent me this Google Doc, like five or six pages of written things , and I took a few days to digest it and find the strength to say, “Okay, I’m ready to support you and properly react and be there for you.” That wasn’t just because he was my husband, but three or four years before he even told me about this I actually wanted to make a film about this very same issue in his hometown, Qom, because I was like, okay the fact that these people in this city are putting so many restrictions on women, this is going to do the opposite and the threat is going to shift to children.

So I started talking to all these boys who had been sexually assaulted and I wanted to write a fictional script. I heard so many horrible stories there, that so many boys were assaulted, and it was so heartbreaking for me when Hossein told me to realise in that moment that he was one of those boys, and that I couldn’t support him for almost 10 years of our relationship because I didn’t know. So that was a hard part for me, but after taking a few days I was like, “I’m ready, let’s have a conversation.”

One of the less spoken about impacts of abuse is the impact it has on people supporting a survivor in their lives, and the supportive relationship between you as husband and wife comes across beautifully in the film. Was it also important for you to show what it’s like to be in a relationship with someone who has experienced abuse?

Elahe: Yes, exactly. The film speaks about a story that happened a long time ago, but the film is about, okay, so what should we do now? How can we support people and educate ourselves and others to give them the support they need? I also wanted to flag the issues that lead to this moment, like lack of education as parents. When Hossein was eight or nine, he told his mum and she didn’t do anything because she probably just didn’t know what to do. She was only 16 years old herself when she had children. She had a lack of education on these issues, which makes it so difficult to face for others.

I think that was the main thing for me in making this film, and it’s such a universal thing. It doesn’t matter if you’re in Iran, in Brazil, in Sweden, wherever you are. If you are a victim of sexual violence you need that support from your surrounding, your family, friends.

Hossein: We talk a lot about the fact that sexual violence exists and the fact that we need to stop it happening, but we rarely educate ourselves about how to support the victims. So, I think it’s great that the film tries to show that from different angles. We wanted to pose that question, are you ready to support your children if this happens to them? Are you educated? If someone sees the film and then goes and educates themselves then we have achieved a very good goal.

Something that was very obvious in the scenes where you’re telling your family is that they clearly love you very dearly and do want to support you, but don’t necessarily know how.

Hossein: Exactly. I thought it was interesting that with my mother, it was obvious to her that I was distressed and she asks my brother to get me a blanket. She knows she has to do something, but she just doesn’t know what it is. She is thinking of options, how do I support my child as a sexual violence victim? And she doesn’t want to talk about it because it’s a very big taboo, but at the same time she wants to emotionally support me. So when she tells my brother to fetch me a blanket, that was really meaningful and heartwarming to me, as a sign that she really does want to support me emotionally, she just doesn’t know what she has to do.

Talking about your close family, over the years did you have a feeling of responsibility to keep quiet about what happened to you in order to keep the peace?

Hossein: I think yes. This question, why my mother didn’t do anything when I was eight and told her I had been abused, was a very important question in my life and I really wanted to know the answer. And there were years where I told myself that I was going to forget all of these things, that I’m just fine, but even in those moments I would be reminded, why didn’t she do anything? I wanted to know the answer and talk about these things, but I was like, what’s the benefit of talking about this? Why would I want to ruin this happy, loving environment that we have? What if they think that it’s their fault? I don’t want them to feel bad. All of these questions were in my mind and stopping me.

So when my therapist said that I need to talk about this with my parents, I shouted all of these questions at her, like, what’s the benefit of talking with my parents about this? I don’t want them to feel blame. And she took a long time to convince me that by speaking about it I’m not blaming them, I’m going to talk about my emotions with them and move forward with these things. The fact that I’m not having my ideal connection with them is much more harmful than the harm that I think I’m going to cause by talking to them about it. She took a long time to speak to me about how I can navigate the conversation. But indeed, it was a big concern for me all these years.

Was it more or less daunting to tell your parents about what happened to you for the first time on camera?

Hossein: I think it was definitely a harder decision. We didn’t tell my parents that this is what we were going to talk about so I was very stressed about the fact that I was going to tell them on camera. So personally it was harder and in terms of production there were a lot of other concerns as well. Even until the last moment I told them I was hesitant on whether it was the right thing to do or not, but what made me more motivated to do it is, whatever happens here, at least it’s something I can share with others who may be able to feel less alone through the film. So it was hard of course, but it was also a motivating factor too, to think that it will establish some conversations around it for people who need it. Do you want to share anything about that?

Elahe: I mean, it was probably the hardest thing that I’ve ever shot because I didn’t know how your parents would react, first to the story and secondly being filmed while it happened. We wanted it to be as intimate and safe as possible for the family, so it was just me and one of my colleagues on set. I had this dual responsibility as both as his partner and the filmmaker, and knowing how important it was for him to make this film. I’ve never seen him in the past 12 years that distressed as he was in that moment, but I tried to say, “It’s going to be okay. Just be calm and let it flow naturally. However feels right to you, we’ll do that.” So it was really hard in all aspects.

How did you feel about your parents’ reaction once you told them?

Hossein: Well when I told them first and they changed the subject, it was really hard for me. I was like, how many years has it taken for me to come up with this decision to talk to them? And then now they are just ignoring this, again? So it was very hard for me and that’s why you see that I get very emotional in this scene. I realised I couldn’t understand one word of that conversation. The first time I recognised that they were talking about jewellery was when I saw the film. So when my mother reacted to seeing how distressed I was and asked my brother to get a blanket, it was a sign for me that they want to do something, so that reaction was heartwarming and let me know that I can ask this question again.

Elahe: And we understand the taboo, how hard it is for them to talk about this and openly accept that their son was assaulted. And they were probably worried how it will impact his future if others know that he was sexually assaulted, which in that culture is the worst thing that could happen to a man. I even remember after the filming finished and they realised this was the case, his dad was worried and said, “you better know that if you publish this film that your wife might divorce you.”

Hossein: Yeah, he told me, “You don’t understand, if you publish this people will judge you differently. People in your work or family will judge you differently. It might even happen that your wife will divorce you.”

Elahe: So, this was their mindset at least when they first heard it. So you can understand the consequence of this kind of thinking would be it is better to ignore it and talk about jewellery instead.

You can understand that your father’s attitude comes from wanting to protect you, but it does emphasise the stigma that is attached to sexual violence and the harm that staying silent does to people who have experienced it.

Hossein: Yes, we did want to challenge that stigma with the film. It was really interesting that after one of the screenings in a Q&A, a middle aged man raised his hand and he said, “You thought that if you talked about this you would be a weak man, however you are now a more strong and braver man.” So I think it’s heartwarming for us to see that it is being received by audiences in this way. This is a stigma that needs to be broken and you should not blame yourself, so if we can contribute to breaking this stigma then that is another goal we will have achieved.

Another thing you show in the film is the pressure put on you both by the family to have children. Do you think experiencing assault as a child has had an effect on your feelings about being a parent yourself?

Hossein: Definitely. We mention in the film that we migrated several times from Iran to Netherlands to the UK, and part of the reason for this migration was if we go to another city or continent that perhaps there will be a better situation for children there. But then you find that this issue exists everywhere. That’s what made me realise that I need to face this issue rather than fleeing from one city to another. It was really hard for me.

Elahe: I think that’s so interesting, because to me, your parents are loving, caring parents and I think you feel the same. Seeing them failing in protecting you as a kid will raise this question in you, that what would you do?

Hossein: Yes, if my parents couldn’t protect me, how could I protect my children? And I think Elahe tried to show this in the film, that I’m really good with children and would love to have children. But this side effect is making me very hesitant of having children.

Now that you’ve made this film together confronting such a personal story, have you found that process has made your relationship stronger?

Hossein: For me, the film was about how Elahe supported me on this journey in the film, and I don’t know if I could have done that and talked to my parents if Elahe wasn’t there. She was really supportive and I’m really thankful to her for that. I couldn’t do this without her. The fact that we wanted make this into a film, she was all the time trying to make sure that I felt safe and that it was safe for my family to make it into a film. We tried to make sure that the film is not going to harm them or me. Elahe was very aware of those situations and I can’t imagine how difficult it was for her to have this dual responsibility as a filmmaker and my wife.

For me, the film was a story about how she as a powerful woman empowered both of us, to go on this journey with the film to try and end these stigmas.

Elahe: For me, it was literally a milestone in our relationship, because when he told me first and after a few weeks or months of conversation we decided to make a film. Then after that it took months to convince him that he should talk to his parents and he was hesitant. The fact that there was no rush or push on my side and he took his time to make this decision himself when he was ready to do that, that helped the process a lot. It took a long time, but I’m glad that we did that and I’m honoured that you told me that and you trusted me.

Finally, what impact do you hope this film will have?

Elahe: For me, the most important outcome will be it reaching audiences around the world and then opening up conversation between people. It’s so rewarding and I tear up when I receive an email from someone saying, “I watched your film and found it so moving, I felt really connected with it and it’s opened up conversations with my friends. We’ve been talking about it for day.” I think that’s the most important thing for me, that people start these conversations and think that if the people on the screen don’t know what to do, that they have time to educate themselves now. You know it’s not an easy thing to deal with. Having these valuable conversations is start of that change.

Hossein: I think if the film can start raising a question around things like male victims of sexual violence, or toxic masculinity, supporting survivors, or if they are from Middle East for example, that actually by violating women’s we’re not making things safe, then that’s a good achievement. If it raises the question, are you educated enough to support people, then that’s a good achievement. If people are dealing with toxic masculinity and someone asks themselves how we can redefine masculinity, that’s a good thing. As Elahe mentioned, I think if people start having conversations by asking themselves questions raised in the film, then that’s a great achievement.

Learn more about Can I Hug You? at www.canihugyou-film.com

Stay up to date with Hossein and Elahe on Instagram below:

Can I Hug You? was developed as part of One World Media’s Global Short Docs Forum. Learn more at www.oneworldmedia.org.uk